1909-1961

Lock opens, serves as maritime economic engine for 52 years

1961

Lock Closes

1968-1973

Gary Hebert saves Lock & bayou from demolition; named to Nat. Register of Historic Places

1978-1982

Lock site transformed into state historic site

1990s-2011

State budget cuts impact operation; Parish, City sign CEAs with state to continue operations

2011

Friends of the Plaquemine

Lock (FOL) established2023

FOL launches campaign for state funding needed for restoration

2023

FOL gets $500,000 in state

funds, local funding follows2024

FOL Lock Restoration Project begins

The grand vision to build the Plaquemine Lock was proposed in the 1860s, and it was considered a monumental task. It involved not only building a Lock, but creating a deeper channel for about 7 miles of Bayou Plaquemine and part of Grand River, which was unnavigable for larger boats in some areas.

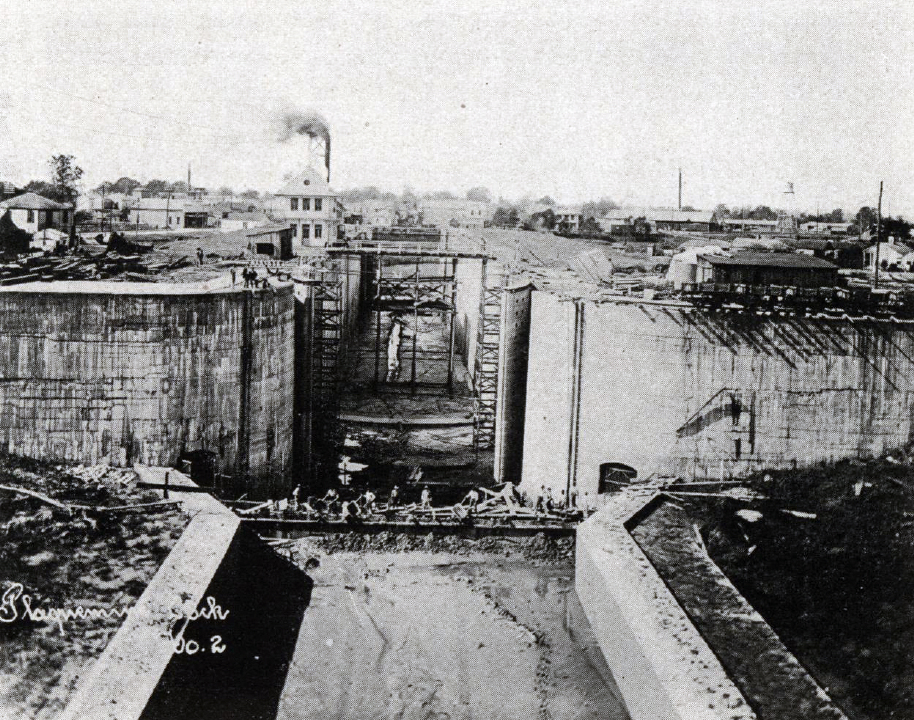

The work to deepen the channel started in the 1880s, and continued into the early 1900s due to numerous problems encountered. But building the Lock structure 55 feet wide and walls 42 feet high, with shifting ground and the fluctuating levels of the river was a much more complex and difficult project.

Almost as soon as construction on the Lock began in 1895, the engineers and contractor began encountering problems with shifting ground, which occurred again in 1897.

Also in 1897 a breach of the Mississippi River levee and the high level of the river required revising the plans to increase the height of the Lock walls from 42 feet to 52 feet high. Another breach of the levee occurred in 1900.

Finally, 5 years after construction began, the floor and walls of the Lock were completed, but another crack occurred at the foundation and the Lock walls began to spread. This presented huge problems and stopped construction. The project was further hampered by the yellow fever epidemic.

When the lock gates were finally erected in 1906, the clearance under the gates, which was supposed to be 6 inches, had diminished to 2 inches because the center floor of the lock had risen. More adjustments were made and finally the Lock was completed in 1909, 14 years after construction began.

The grand vision for the Lock was finally achieved 40 years after it was first proposed. Upon its completion, the lock had the highest lift in the United States, and was considered an engineering marvel.

In addition, the Lockhouse -an exquisite one-of-a-kind building in all of the United States – featured a unique Dutch design with gleaming white tile and huge wooden windows, was considered in itself an architectural gem.

The Lock proved to be the economic engine many thought it would be. It transformed Plaquemine from a sleepy, small town into a major maritime transportation route. With it came docks, hotels, restaurants, theaters, mercantile stores and more.

In 1917, 2,300 boats traveled through the lock. By 1930, 3,925 boats traveled through the lock. But as barges grew longer, the turns in Bayou Plaquemine became a major drawback and it closed 52 years after it opened in 1961.

The lock, which had been built and operated by the US Corps of Engineers, closed the site and boarded up the Lockhouse. By this time in the early 1960s, Dow Chemical Co. had come to Plaquemine, bringing a new industrial economy and people to the city. This produced traffic back-ups, and in the late 1960s the La. Department of Transportation proposed tearing down the lock and filling in a large section of Bayou Plaquemine from the Mississippi River to past the railroad bridge to make way for a highway through the city.

Local editor Gary J. Hebert could not fathom destruction of the lock, lockhouse or the bayou. In fact, his grand vision was for the Lock site to become a major park and tourist attraction. He received almost no support for his vision. People just wanted the quickest end to their traffic problems.

But, he fought, using his newspaper and every other tool he could muster, from the late 1960s until 1973, to stop the state plans for the highway. It cost him a ridicule, battles with local and state officials, and a large amount money as angry business owners boycotted the newspaper. But he eventually won when he had the Lock site, and with it a portion of the bayou, put on the National Register of Historic Places. This designation meant it could not be demolished.

During his battle he gained the support of Dean Gerald McClendon, head of LSU’s landscape architecture program, and together they laid out a plan for the park and tourist attraction. Once it was determined that the site could not be

demolished, Hebert turned to state and local officials to join his vision for a park. That took years more, but in 1978 the site was turned over to the state and $2.5 million was allocated to the La. Office of State Parks for the transformation of the site into a state park and tourist attraction – the Plaquemine Lock State Historic Site. It opened, with great fanfare, in 1982.

State budget problems in the late 1990s and early 2000s put the Lock site in flux, as the state proposed closing and boarding up the site. With pressure from local residents who could not imagine the site being boarded up, Iberville Parish and the City of Plaquemine signed on with the state in 2011 for its continued operation. Their Cooperative Endeavor Agreement called for the state to handle maintenance and insurance, the parish would provide tour guides, and the city would handle grounds maintenance and utilities

The same year Friends of the Lock was formed. This group became the guardian of the Lock – making sure that it was being cared for and promoted.

Why the Lock is Unique:

Economic Catalyst:

The Lock was the catalyst of Plaquemine’s growth and development from the early 1900s to the 1960s. Its importance as a critical maritime transportation route transformed Plaquemine from a small town to a bustling hub of economic activity.

Engineering Feat:

t: At the time of its construction, the Lock boasted the highest lock lift in the United States, an astounding 51 feet. It was considered a marvel of early 20th-century engineering.

Blueprint for the Panama Canal:

The Lock was designed by Col. George Gothels, the visionary engineer behind the Panama Canal. Many experts believe that the Plaquemine Lock served as a prototype for the Panama Canal.

Architectural Gem:

The Lockhouse’s design is unparalleled in the United States. Its Dutch style and striking features, including its gleaming white tiles and huge, round cypress windows, make it an architectural treasure worth preserving.

Tourism & Recreational Importance:

The 2024 restoration of the Lockhouse includes a major upgrade of the visitor experience at the Lockhouse. The 1970s exhibits will be replaced with new museum-quality exhibits and interactive exhibits that bring it up to modern standards. As funds become available, upgrades will also be made to the boathouse and grounds. These projects will increase tourism and also add to the local recreational importance of the site.

Soul of the Community:

y: The Lockhouse is the crown jewel of Plaquemine’s beautiful downtown area, the city’s major tourism draw, and an integral part of the city’s most unique recreational area. It is the symbol of the city’s rich history and community pride.

Transformative impact of the Lock: The Plaquemine Lock was a game-changer in maritime transport, cutting the travel distance from the Mississippi River to the heart of Louisiana, New Orleans and the Gulf by approximately 180 miles- saving significant time and fuel. In addition, numerous trading posts dotted the route, making it a CRITICAL transportation and shipping route.

With thousands of boats using the Lock annually, theaters, restaurants, hotels, mercantile and other businesses sprang up to cater to the growing town. By 1917, the Lock was incredibly busy, with more than 2,300 boats passing through, carrying 205,0000 tons of freight. By 1930, 3,925 boats traveled through the lock.

It remained an extremely important, and busy, shipping route until its closure in 1961, when the Port Allen Lock opened and provided much easier maneuverability for longer barges.